Junior laments lack of Asian representation in curriculum

February 11, 2022

Growing up, I could barely find any Asian American representation in textbooks. Whether it is in humanities, whether intended or not, social sciences, or STEM fields, the American education system gives off the impression that there are no prominent Asian figures worth learning about. Even when students do learn about Asian Americans in the Gold Rush or the War World II, the actual Asian experience was not recognized. I, like other students, could not find myself in books I read and the movies I watched. Occasionally, I saw Asian characters on TV — people like Lane Kim from Gilmore Girls and Nelly Yuki from Gossip Girl. To my surprise, the two were insanely similar: they both fit perfectly into the model minority. This stereotype depicts Asians as reticent, submissive and further perpetuates the narrative in which Asians are born smart, obscuring racism against Asian Americans.

While the pandemic worsened, Asian Americans faced a double threat: not only the spreading deadly virus but also growing discrimination. Along with the Atlanta spa shootings, a racially motivated shooting spree that killed eight people, six of whom were Asian women, Asian-based hate crimes became increasingly common. For weeks, I watched masked protestors march down the streets of Minneapolis and New York City, calling for justice and structural accountability. Captivated by witnessing history, I knew to remember those packed streets as a symbol for change in the flawed justice system.

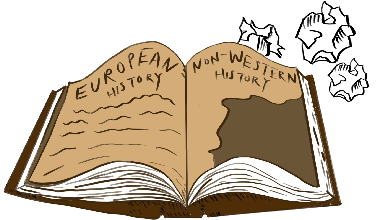

The root of anti-Asian racism essentially lies within the gap that is too often filled with prejudice and ignorance — the western education system. In particular, the American education system has remained largely Eurocentric, outdated, and disconnected from reality; the silence and disengagement perpetuate systematic racism. The surge in anti-Asian hatred during the COVID-19 pandemic is a historical trend and understanding the history of it comes before addressing the problem itself.

It is incumbent upon the Greenhills faculty to help students of color feel more valued in the classrooms, amplify issues of marginalized groups, and adopt a more inclusive overall curriculum that better reflects the nation’s diverse history.

There are many prominent events that lay on the spectrum of Asian history beyond the textbooks. Aside from the Opium War that students learn about in 9th grade Global Perspectives, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and Japanese internment camps during World War II in US history, there is so much more to it. Most of us don’t, for example, learn about the mob violence faced by Asian immigrants, nor do we celebrate Patsy T. Mink as the first Asian American woman, and the first woman of color, to serve in Congress.

The school should still make an effort to ensure that books and films students read and watch in class cover a range of topics, including Asian food, music, and arts. Students should not only be learning about Asian culture in social science and language classes — ethnic studies are interdisciplinary and permeate every subject. For example, students in art electives can learn about Ai Weiwei, a Chinese contemporary artist known for utilizing his installation art, eclectic oeuvre to speak up against corruption. Increased overall representation galvanizes more visibility around anti-Asian racism and establishes a collective conscience of diversity. The study conducted by Christine E. Sleeter from the National Education Association The Academic and Social Value of Ethnic Studies also suggests that well-designed and well-taught ethnic studies curricula cast positive academic and social outcomes for students.

In addition to a more inclusive curriculum, recruitment and retention of qualified teachers of color can also boost students’ performance. At Greenhills, there are only two Asian teachers in the building, and both are under the modern and classical language department. This means that in determining the general curricula at Greenhills, no Asian voice is represented. While the Diversity and Inclusion team at Greenhills actively works towards building a safe environment for all students, teachers from different backgrounds and cultures can draw from their own experiences and connect better with students alike.

Ethnic studies serve as a big umbrella term that encapsulates not only Asian studies: it informs and examines different histories, cultures, and issues of racially marginalized groups. As the American education system continues to emphasize the predominantly European narrative, Greenhills has the responsibility to assure that courses offered dismantle systemic racism. Whether it is about Black, Latine, Native, Asian, or LGBTQIA+ studies, the topic of culture and prejudice should be discussed in the everyday classroom setting to further raise awareness and destigmatize this difficult conversation.